Nearly 38% of the U.S. adult population has prediabetes.<sup>1</sup> While prediabetes is a common condition, it can lead to serious problems. If you are diagnosed with prediabetes, excessive glucose in your bloodstream may be damaging the inner lining of your blood vessels, increasing your risk for cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, and abnormal triglycerides, so it is important to understand how your body responds to glucose and under what conditions your blood sugar spikes. Repeated spiking of blood sugars puts stress on the pancreas, increasing the risk of insulin resistance.

Even without having type 2 diabetes, you can track your blood glucose via a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) and have real data to show how your body responds to the foods you eat. You can also see how chronic stress and exercise affect your blood glucose.

Insulin resistance and prediabetes are warning signs that unless you can change some of your risk factors, you are likely at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes. The good news is that insulin resistance and prediabetes can be reversed, allowing you to live a longer, healthier life.

What is Insulin?

Insulin and glucagon are two hormones secreted by the pancreas that regulate blood sugar. These two hormones maintain homeostasis. Insulin is released by beta cells in the pancreas when blood glucose levels are high following a meal. Insulin secretion is typically pulsatile and biphasic, with a rapid initial phase followed by a longer and less intense phase.<sup>2</sup>

Insulin directs insulin transporter (GLUT 1-5) molecules in the cell membrane to shuttle glucose into your liver, muscle, and fat cells to be used as fuel for each cell’s metabolic activity or to be stored as glycogen in muscle or liver cells. Moving glucose into the cells and out of the bloodstream helps keep blood sugar levels stable.

Insulin transporters are sensitive to blood glucose levels. More sensitive transporters can be found in the brain and kidney. Less sensitive ones are found in muscle and fat. This allows muscle and fat to absorb glucose into their cells when blood glucose levels are high after a meal and promotes fat breakdown (lipolysis) when blood glucose levels are low.<sup>2</sup>

When blood glucose is too low, glucagon is released to restore homeostasis.

This balancing act is not as straightforward as it seems because many factors can influence blood glucose.

Factors that can affect blood glucose: <sup>2, 3, 4</sup>

- Fats

- Amino acids, especially arginine, L-ornithine, and leucine

- The sympathetic nervous system

- Growth hormone, incretins, and cortisol

- Gut peptides

- Some medications

- Infections

- Menstrual cycle

- Alcohol

- Dehydration

- Genetic variations in insulin production and utilization

<p class="pro-tip">Insulin and glucagon work together to regulate blood sugar. Insulin lowers blood glucose, and glucagon raises it.</p>

What is Insulin Resistance?

Increased caloric intake and decreased physical activity resulting in the gain of metabolically active adipose tissue is the primary cause of insulin resistance. Although weight gain can lead to insulin resistance, it isn’t the only factor. There are complex metabolic pathways involving the liver, white adipocytes (fat cells), skeletal muscle, and metabolites produced by these cells that result in insulin resistance.<sup>5</sup>

Insulin has the following effects on cells:<sup>5</sup>

- Increases glucose uptake into skeletal muscle and fat cells

- Increases glucose uptake into the liver to be stored as glycogen

- Suppresses the conversion of fats and amino acids to glucose in the liver

- Suppresses the breakdown of fat in adipose tissue

- Suppresses glucagon release from the pancreas

When the pancreas needs to work harder to produce enough insulin to regulate blood sugar, this is called insulin resistance. The beta cells in the pancreas will eventually either burn out completely or be unable to compensate for the increased demand. Insulin resistance is a predictor of future type 2 diabetes. However, insulin resistance is readily reversible with fat loss and a diet and exercise plan that focuses on minimizing spikes in blood glucose.

<p class="pro-tip">When fat, muscle, and liver cells become insensitive to insulin (insulin resistance), blood glucose levels rise, inflammation increases and when the pancreas can no longer compensate, type 2 diabetes develops.</p>

The Relationship Between Glucose and Insulin Resistance

Glucose is a simple sugar that provides cellular energy after being converted to adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Some cells, like brain cells, rely on a steady stream of glucose to survive. However, other cells can use alternate forms of energy that are ultimately converted to glucose in a process called gluconeogenesis. The more metabolically flexible your cells are, the more they can use alternative energy sources.

Insulin primarily affects muscle, liver, and white fat cells. Muscle cells take up the majority of excess blood glucose when they are sensitive to insulin. The process of developing insulin resistance is thought to be:

- Muscle cells become inflamed from excess fatty acids.

- As muscle cells become resistant to insulin, excess blood glucose is returned to the liver and used to produce lipids and circulating free fatty acids.

- Insulin suppresses lipid breakdown in fat cells. When fat cells become resistant to insulin, free fatty acids increase in the blood.

- Higher free fatty acids in the blood affect liver and muscle metabolism, making them more insulin resistant.

- Excess free fatty acids are deposited as fat in the liver, muscle, and adipose tissue.

When fat cells under the skin become “over”full, fat is deposited between organs in the abdomen. These fat cells have a decreased blood supply and, as a result, develop low levels of inflammation. The fat cells release chemicals that increase insulin resistance, and insulin resistance increases fat deposition, leading to a vicious cycle.<sup>6</sup>

<p class="pro-tip">Insulin resistance develops when muscle, fat, and liver cells become less sensitive to insulin. Insulin resistance increases fat deposition, which increases insulin resistance in a downward-spiraling cycle unless steps are taken to normalize blood sugar.</p>

{{mid-cta}}

Symptoms of Insulin Resistance

There are usually no symptoms to indicate that you are insulin resistant. However, these changes may be occurring in your body and are the effects of insulin resistance: <sup>7, 8</sup>

- High blood sugar

- High blood pressure

- Abnormal lipid metabolism

- An increase in visceral fat

- High blood uric acid levels

- Increased inflammation

- Increased risk of blood clots

When your muscle, liver, and fat cells do not respond to insulin as well as they should, blood glucose levels increase. Increased blood glucose damages the inner lining of blood vessels, making your heart pump harder to overcome the resistance imposed by narrowed and scarred blood vessels. Increased friction along blood vessel walls can also increase the risk of blood clots.

If insulin resistance is severe, patches of dark, velvety skin on the back of your neck, elbows, knees, knuckles, or armpits may develop. This discoloration is called acanthosis nigricans.<sup>9</sup>

As insulin resistance progresses, it can lead to metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, hypertension, abnormal blood lipids, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.<sup>10</sup> Of these, the most common consequence of uncontrolled blood sugar and insulin resistance is type 2 diabetes. Insulin resistance is thought to precede type 2 diabetes by about 10 to 15 years.<sup>11</sup>

<p class="pro-tip">There are no definitive symptoms associated with insulin resistance. However, if your body mass index (BMI) is over 25 kg/m<sup>2</sup>, or you have increased fasting blood sugar, an abnormal lipid profile, or metabolic syndrome, you are at increased risk of insulin resistance.</p>

Risk Factors for Insulin Resistance

The biggest risk factor for insulin resistance is obesity, especially abdominal obesity<sup>12</sup>, which accounts for 25% to 35% of the variability of insulin activity<sup>13</sup> and 60% to 85% of insulin resistance overall.<sup>6</sup> Increased body fat increases oxidative stress on body cells, which can lead to insulin resistance.<sup>14</sup>

Once insulin resistance develops, it sets the stage for further weight gain. This results in a cycle of weight gain and further insulin resistance until the pancreas can no longer pump out enough insulin to meet the demand.

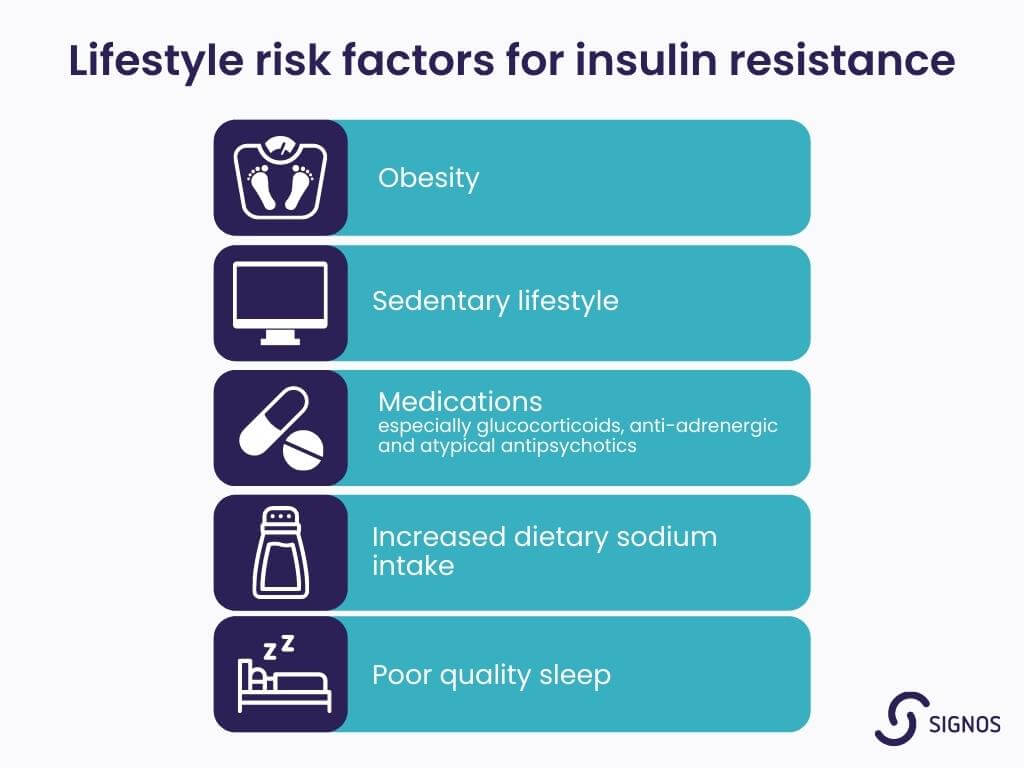

Modifiable Risk Factors

Lifestyle risk factors for insulin resistance:<sup>9, 15, 16, 17</sup>

- Obesity

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Medications (especially glucocorticoids, anti-adrenergic and atypical antipsychotics)

- Increased dietary sodium intake

- Poor quality sleep

Non-modifiable Risk Factors

Genetic conditions associated with increased insulin resistance:<sup>11</sup>

- Myotonic dystrophy

- Werner syndrome

- Lipodystrophy

- Ataxia-telangiectasia

- Type A insulin resistance syndrome

- Type B insulin resistance syndrome

Other non-modifiable risk factors:<sup>9, 18, 19, 20</sup>

- Over age 45

- Non-Caucasian ethnicity

- Family history of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

How Is Insulin Resistance Diagnosed?

The most direct measurement of insulin resistance is a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic glucose clamp technique. This technique is used in diabetes research but not as a diagnostic test. In this test, both glucose and insulin are infused via an intravenous line (IV). Researchers measure the amount of glucose infused to reach a steady state to determine the degree of insulin resistance.<sup>5</sup>

Other tests that may serve as a surrogate for measuring insulin resistance include: <sup>5, 6, 11, 21</sup>

- Homeostatic model assessment insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) ratio less than 1.8

- Post-glucose challenge tests such as the Frequently Sampled Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test

- Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index (QUICK1)

- Serum triglyceride: People with prediabetes and triglycerides greater than or equal to 150 g/dL are more likely to have insulin resistance. The optimal cutoff is 130 mg/dL

- Triglyceride/HDL ratio: Men with a ratio greater than 3.5 or women with a ratio greater than 2.5 are more likely to have insulin resistance. This correlation only seems to hold up in Caucasian individuals

- Insulin concentration of less than 15 mU/l2 (<110 pmol/l) in people of normal body weight or less than 25 mU/l2 (<180 pmol/l) in people who are obese

<p class="pro-tip">Doctors don’t usually test people for insulin resistance as the methods are complicated and used mainly for research. Instead, they measure fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C. Both are tests for prediabetes and diabetes, potential outcomes of insulin resistance.</p>

Insulin resistance is a risk for women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Read this guide about PCOS and weight loss for more information.

What is Prediabetes?

Prediabetes is when your blood glucose is higher than it should be, but not high enough to meet the criteria for diabetes. Increased blood glucose can be due to inadequate insulin production or insulin resistance.

Over 96 million American adults have prediabetes. This is one in every three adults. Of those with prediabetes, more than 80% are unaware.<sup>22</sup>

Insulin resistance leads to increased blood glucose, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes, but it is not the only cause of prediabetes, and the progression can be reversed.

<p class="pro-tip">Prediabetes is an intermediate stage between having normal glucose tolerance and full-blown type 2 diabetes.</p>

Symptoms of Prediabetes

There are no symptoms of prediabetes. However, the changes that are occurring in your body if you are diagnosed with prediabetes are due to increased blood glucose and, therefore, are like the ones seen with insulin resistance.

As your blood glucose level increases, you may develop the symptoms associated with chronic high blood sugar levels:

- Increased thirst

- Increased urination

- Fatigue

- Blurred vision

- Headaches

- Slow-healing cuts and sores

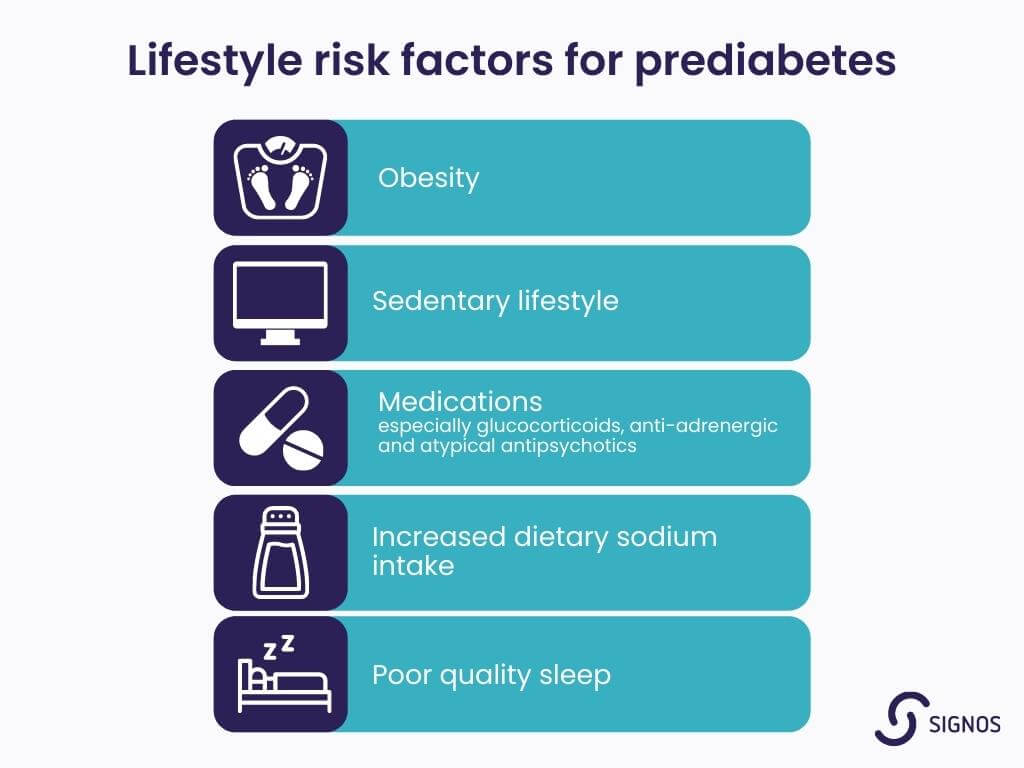

Risk Factors for Prediabetes

The risk factors for prediabetes are the same as for insulin resistance.

How is Prediabetes Diagnosed?

Prediabetes is diagnosed by looking at your fasting blood glucose.<sup>23, 24</sup>

Fasting Blood Glucose

- Normal = between 70 and 99 mg per dL

- Prediabetes = between 100 and 125 mg per dL

- Diabetes = 126 mg per dL or higher

If your fasting blood glucose is high, your doctor may suggest a hemoglobin A1C test which measures your average blood glucose levels over the previous three months.<sup>24</sup>

Hemoglobin A1C

- Normal = below 5.7%

- Prediabetes = between 5.7% and 6.4%

- Diabetes = 6.5% or higher

Another test that is used to determine your degree of hyperglycemia is an oral glucose tolerance test: 25

Glucose Tolerance Test

- Normal: 139 mg/dL or lower

- Prediabetes: 140 to 199 mg/dL

- Diabetes: 200 mg/dL or higher

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offer a Prediabetes Risk Test.<sup>25</sup>

<p class="pro-tip">Prediabetes is diagnosed by checking your fasting blood glucose levels and hemoglobin A1C or doing a glucose tolerance test if your fasting blood glucose is high. You may have prediabetes and not experience any symptoms.</p>

Insulin Resistance vs Prediabetes

Insulin resistance is a metabolic process in the body that contributes to several diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome, and polycystic ovary syndrome.

Prediabetes is a medical diagnosis based on elevated fasting blood glucose levels. Prediabetes can occur when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin, the insulin is not functioning correctly, or body cells are resistant to the effects of insulin (Insulin resistance).

Prediabetes is along the continuum of hyperglycemia without meeting the criteria for type 2 diabetes. Therefore, it is important to identify people who have hyperglycemia so they can take steps to reduce their blood sugar and prevent the complications associated with type 2 diabetes. This is why people at risk may want to consider tracking their blood glucose via a continuous glucose monitor (CGM).

There is some controversy about the definition of prediabetes (cutoffs for blood glucose) and whether there is a stronger association between prediabetes and insulin resistance in the liver when compared to prediabetes and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle, but the link between insulin resistance, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes is clear.<sup>26</sup>

Metabolic syndrome identifies people at higher risk of cardiovascular disease as a consequence of insulin resistance.<sup>2</sup> Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance rarely cause symptoms which means that many people with these conditions are unaware of their risk. Prediabetes may cause some of the symptoms associated with diabetes.

Metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and prediabetes are all risk factors for type 2 diabetes. All three of these conditions are characterized by persistently increased blood glucose.

<p class="pro-tip"><strong>Learn more: </strong> <a href="/blog/signs-metabolic-health-out-of-balance">six signs your metabolic health is out of balance</a>.</p>

How to Reverse Insulin Resistance

The best way to reverse insulin resistance is to understand your blood glucose levels and set weight loss goals. Optimizing your metabolic health is a lifelong endeavor and is a priority for anyone who wants to maximize their number of disease-free years.

.jpg)

Choose a Healthy Diet

A healthy diet can decrease peaks in blood glucose and insulin secretion after meals, increase glucagon secretion, and improve insulin sensitivity.<sup>26</sup>

Dietary recommendations include:<sup>2, 3, 6, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31</sup>

- Consume a diet with 30% of calories from protein, as proteins can help reduce the glycemic response to carbohydrates in your diet

- Lose 5% to 10% of baseline weight

- Moderate alcohol consumption

- Minimize consumption of simple and processed carbohydrates

- Decrease saturated fats as they increase inflammation and increase insulin resistance

- Choose carbohydrates with a low glycemic index and combine them with fiber

- Choose foods that are excellent sources of magnesium, chromium, and zinc as they may decrease insulin resistance and improve the effects of insulin

<p class="pro-tip">Learn about slow-digesting carbs and why you should avoid ultra-processed foods</p>

Increase Your Physical Activity

Increased physical activity can:<sup>32</sup>

- Reduce insulin resistance

- Increase muscle mass which can then absorb more glucose from the bloodstream

- Open gateways for glucose to enter muscles that are not insulin-dependent

Skeletal muscle pulls glucose from the blood to use as an energy source. In addition to the glucose transporters found on skeletal muscle, other signaling molecules increase glucose uptake independently of the insulin pathway. Exercise increases glucose uptake into skeletal muscle by 50-fold.<sup>33</sup>

Get Adequate Vitamin D

People who are obese or overweight and are insulin dependent or pre-diabetic are often deficient in vitamin D.<sup>6</sup> Vitamin D helps regulate insulin secretion, increase insulin sensitivity, and reduce inflammation.<sup>34</sup>

The Institute of Medicine recommends that adults 19 to 70 take 600 IU of vitamin D per day, with an upper limit of 4,000 IU. Adults over 70 should bump this up to 800 IU per day.<sup>35</sup>

The Endocrine Society recommends that adults aged 19 and older take between 1,500 to 2,000 IU per day with an upper limit of 4,000 IU for adults under age 70 and 10,000 IU for those over age 70.<sup>36</sup>

Improve Your Sleep Habits

Disrupted or insufficient sleep can increase your risk of metabolic syndrome, high blood pressure, abnormal blood lipids, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.<sup>18, 38</sup> In one study, partial sleep deprivation for just one night increased insulin resistance in healthy people.<sup>38</sup>

How to Prevent Insulin Resistance

Achieve and Maintain a Healthy Weight

The prevalence of prediabetes is higher in people who are overweight. In one study, more than 80% of people with self-reported prediabetes were overweight or obese. However, only half of those with self-reported prediabetes were actively trying to lose weight or increase physical activity.<sup>39</sup>

In another study, researchers found that weight loss alone improves insulin sensitivity and therefore decreases your risk of prediabetes. Physical activity alone did not improve insulin sensitivity in the long term. To get continued improvement in insulin sensitivity, weight loss and physical activity are both needed.<sup>40</sup>

Increase Physical Activity

In studies conducted in China, Finland, the United States, and India, over a 3 to 6 year period, participants who used dietary modifications plus increased physical activity were able to reduce the incidence of diabetes by 28% to 58% compared to a placebo group that made minimal to no changes.<sup>41</sup>

Even though more than one-third of U.S. adults have insulin resistance, nearly 90% are unaware because of the lack of symptoms.<sup>1</sup> Unfortunately, counting calories alone will not give you much information on how your body is using glucose. It also does not tell you which lifestyle modifications are most likely to improve your glucose levels.

Use a CGM and App

One exciting/interesting/novel way to prevent or reverse insulin resistance or prediabetes is to track your blood sugar using a continuous glucose monitor. Tracking your blood sugar can help with your weight loss journey. The data you receive can be combined with activity data from your favorite fitness app to provide a comprehensive feedback system to help you prevent or reverse insulin resistance.

- Item 1

- Item 2

- item 3

Topics discussed in this article:

References

- National Diabetes Statistics Report | Diabetes | CDC. (n.d.). CDC. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/

- Wilcox G. (2005). Insulin and insulin resistance. The Clinical biochemist. Reviews, 26(2), 19–39, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1204764/

- Nakrani MN, Wineland RH, Anjum F. Physiology, Glucose Metabolism. [Updated 2021 Jul 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-., from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560599/

- American Diabetes Association. (n.d.). Factors Affecting Blood Sugar. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://professional.diabetes.org/sites/professional.diabetes.org/files/media/ada-factsheet-factorsaffectingbloodsugar.pdf

- Gancheva, S., Jelenik, T., Álvarez-Hernández, E., & Roden, M. (2018). Interorgan Metabolic Crosstalk in Human Insulin Resistance. Physiological Reviews, 98(3), 1371–1415. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00015.2017

- Govers E, Slof E, Verkoelen H, Ten Hoor-Aukema NM, KDOO (2015) Guideline for the Management of Insulin Resistance. Int J Endocrinol Metab Disord 1(4): https://dx.doi.org/10.16966/2380-548X.115

- Sasaki, N., Ozono, R., Higashi, Y., Maeda, R., & Kihara, Y. (2020). Association of Insulin Resistance, Plasma Glucose Level, and Serum Insulin Level With Hypertension in a Population With Different Stages of Impaired Glucose Metabolism. Journal of the American Heart Association, 9(7), e015546. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.015546

- Reaven, G. M. (1995). Pathophysiology of insulin resistance in human disease. Physiological Reviews, 75(3), 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.473

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2021, December 9). Insulin Resistance & Prediabetes. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/what-is-diabetes/prediabetes-insulin-resistance

- Berdichevsky, A., Guarente, L., & Bose, A. (2010). Acute Oxidative Stress Can Reverse Insulin Resistance by Inactivation of Cytoplasmic JNK. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285(28), 21581–21589. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m109.093633

- Freeman AM, Pennings N. Insulin Resistance. [Updated 2021 Jul 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507839/

- Lynne E. Wagenknecht, Carl D. Langefeld, Ann L. Scherzinger, Jill M. Norris, Steven M. Haffner, Mohammed F. Saad, Richard N. Bergman; Insulin Sensitivity, Insulin Secretion, and Abdominal Fat: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Family Study. Diabetes 1 October 2003; 52 (10): 2490–2496. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2490

- Reaven, G., Abbasi, F., & McLaughlin, T. (2004). Obesity, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease. Recent progress in hormone research, 59, 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1210/rp.59.1.207

- Berdichevsky, A., Guarente, L., & Bose, A. (2010b). Acute Oxidative Stress Can Reverse Insulin Resistance by Inactivation of Cytoplasmic JNK. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 285(28), 21581–21589. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m109.093633

- Luo, B., Soesanto, Y., & McClain, D. A. (2008). Protein Modification by O-Linked GlcNAc Reduces Angiogenesis by Inhibiting Akt Activity in Endothelial Cells. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 28(4), 651–657. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.107.159533

- Baudrand, R., Campino, C., Carvajal, C. A., Olivieri, O., Guidi, G., Faccini, G., Vöhringer, P. A., Cerda, J., Owen, G., Kalergis, A. M., & Fardella, C. E. (2014). High sodium intake is associated with increased glucocorticoid production, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Clinical endocrinology, 80(5), 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen.12225

- Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. E. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and science of sleep, 9, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S134864

- Andrew Mente, Fahad Razak, Stefan Blankenberg, Vlad Vuksan, A. Darlene Davis, Ruby Miller, Koon Teo, Hertzel Gerstein, Arya M. Sharma, Salim Yusuf, Sonia S. Anand, for the Study of Health Assessment and Risk Evaluation (SHARE) and SHARE in Aboriginal Peoples (SHARE-AP) Investigators; Ethnic Variation in Adiponectin and Leptin Levels and Their Association With Adiposity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes Care 1 July 2010; 33 (7): 1629–1634. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1392

- Steven M Haffner, D'Agostino Ralph, Mohammed F Saad, Marian Rewers, Leena Mykkänen, Joseph Selby, George Howard, Peter J Savage, Richard F Hamman, Lynne E Wegenknecht, Richard N Bergman; Increased Insulin Resistance and Insulin Secretion in Nondiabetic African-Americans and Hispanics Compared With Non-Hispanic Whites: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes 1 June 1996; 45 (6): 742–748.

- Richard S. Legro, Diane Finegood, Andrea Dunaif, A Fasting Glucose to Insulin Ratio Is a Useful Measure of Insulin Sensitivity in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 83, Issue 8, 1 August 1998, Pages 2694–2698, https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.83.8.5054

- McLaughlin, T., Abbasi, F., Cheal, K., Chu, J., Lamendola, C., & Reaven, G. (2003). Use of Metabolic Markers To Identify Overweight Individuals Who Are Insulin Resistant. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139(10), 802. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00007

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, December 21). Prediabetes - Your Chance to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/prediabetes.html

- JWJ Beulens, F Rutters, L Rydén, O Schnell, L Mellbin, HE Hart, RC Vos, Risk and management of pre-diabetes, European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, Volume 26, Issue 2_suppl, 1 December 2019, Pages 47–54, https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319880041

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, March 2). Diabetes Testing. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/getting-tested.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Take the Test - Prediabetes | Diabetes | CDC. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/prediabetes/risktest/index.html

- Sun H. Kim, Gerald M. Reaven; Isolated Impaired Fasting Glucose and Peripheral Insulin Sensitivity: Not a simple relationship. Diabetes Care 1 February 2008; 31 (2): 347–352. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc07-1574

- Muscogiuri, G., Barrea, L., Caprio, M., Ceriani, F., Chavez, A. O., el Ghoch, M., Frias-Toral, E., Mehta, R. J., Mendez, V., Paschou, S. A., Pazderska, A., Savastano, S., & Colao, A. (2021). Nutritional guidelines for the management of insulin resistance. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.1908223

- R W Simpson, J McDonald, M L Wahlqvist, L Atley, K Outch, Macronutrients have different metabolic effects in nondiabetics and diabetics, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 42, Issue 3, September 1985, Pages 449–453, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/42.3.449

- Sampey, B. P., Vanhoose, A. M., Winfield, H. M., Freemerman, A. J., Muehlbauer, M. J., Fueger, P. T., Newgard, C. B., & Makowski, L. (2011). Cafeteria diet is a robust model of human metabolic syndrome with liver and adipose inflammation: comparison to high-fat diet. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 19(6), 1109–1117. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.18

- Funaki, M. (2009). Saturated fatty acids and insulin resistance. The Journal of Medical Investigation, 56(3,4), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.2152/jmi.56.88

- Deborah J. Clegg, Koro Gotoh, Christopher Kemp, Matthew D. Wortman, Stephen C. Benoit, Lynda M. Brown, David D'Alessio, Patrick Tso, Randy J. Seeley, Stephen C. Woods, Consumption of a high-fat diet induces central insulin resistance independent of adiposity, Physiology & Behavior, Volume 103, Issue 1, 2011, Pages 10-16, ISSN 0031-9384,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.01.010

- Hawley, J. A., & Lessard, S. J. (2008). Exercise training-induced improvements in insulin action. Acta physiologica (Oxford, England), 192(1), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01783.x

- Hawley, J. A., & Lessard, S. J. (2008). Exercise training-induced improvements in insulin action. Acta physiologica (Oxford, England), 192(1), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01783.x

- Mitri, J., & Pittas, A. G. (2014). Vitamin D and diabetes. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America, 43(1), 205–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2013.09.010

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2010, November 30). IOM Report Sets New Dietary Intake Levels for Calcium and Vitamin D To Maintain Health and Avoid Risks Associated With Excess. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2010/11/iom-report-sets-new-dietary-intake-levels-for-calcium-and-vitamin-d-to-maintain-health-and-avoid-risks-associated-with-excess

- Michael F. Holick, Neil C. Binkley, Heike A. Bischoff-Ferrari, Catherine M. Gordon, David A. Hanley, Robert P. Heaney, M. Hassan Murad, Connie M. Weaver, Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Vitamin D Deficiency: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 96, Issue 7, 1 July 2011, Pages 1911–1930, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-0385

- Cappuccio, F. P., & Miller, M. A. (2017). Sleep and Cardio-Metabolic Disease. Current cardiology reports, 19(11), 110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-017-0916-0

- Donga, E., van Dijk, M., van Dijk, J. G., Biermasz, N. R., Lammers, G. J., van Kralingen, K. W., Corssmit, E. P., & Romijn, J. A. (2010). A single night of partial sleep deprivation induces insulin resistance in multiple metabolic pathways in healthy subjects. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism, 95(6), 2963–2968. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2009-2430

- Liu, C., Foti, K., Grams, M. E., Shin, J. I., & Selvin, E. (2019). Trends in Self-reported Prediabetes and Metformin Use in the USA: NHANES 2005–2014. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(1), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05398-5

- Bouchonville, M., Armamento-Villareal, R., Shah, K., Napoli, N., Sinacore, D. R., Qualls, C., & Villareal, D. T. (2014). Weight loss, exercise or both and cardiometabolic risk factors in obese older adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. International journal of obesity (2005), 38(3), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.122

- Echouffo-Tcheugui, J. B., & Selvin, E. (2021). Prediabetes and What It Means: The Epidemiological Evidence. Annual Review of Public Health, 42(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102644