Key Takeaways

- Insulin regulates the uptake of glucose in the blood into your cells

- High insulin levels tell your body to store glucose and keep your fat stores locked away

- Lower insulin levels tell your body to mobilize your fat stores to use as energy

- The correlation between insulin and obesity is an area of very active research—controversy remains among the research community about the direct role of insulin in obesity and weight loss

Weight gain happens when you consume more energy (calories) than you need, but energy balance is made up of a lot more than simply ingested calories counted and calories burned via an exercise tracker. You may have heard or read that a relationship exists between insulin and weight. Does it?

Glucose, or sugar, is the most basic form of energy that your body and brain use to power almost all activities. When glucose enters the bloodstream (from foods or drinks we consume), insulin—a hormone that regulates your blood glucose—gets released by the pancreas to help store the extra glucose in the muscles, liver, or fat tissue for later use.

Does insulin make you gain weight? Not directly. Excess glucose that gets converted into fat causes weight gain.

The energy you eat (whether from carbohydrates, protein, or fat) that goes unused is stored mostly as fat. This energy balance is modulated by many things including stress, physical activity, genetics, medications, medical problems, and the environment.

For most people following a Standard American Diet, extra daily energy intake comes from calorie-dense, nutrient-poor foods<sup>1</sup> specifically engineered to make them more delicious. High-carb and high-fat foods with added sugars—especially in the form of “ultra-processed foods”—provide more calories and glucose than your body needs to keep “all systems go,” but often don’t satisfy hunger for long.

They can also cause high glucose spikes that your body processes by releasing insulin, which stops you from burning fat stores as energy, among many other things.

<p class="pro-tip">Read our Guide to Insulin Resistance and Prediabetes</p>

What Is Insulin and How Does It Impact Weight?

Insulin is a hormone that acts as the body’s thermostat for blood glucose. As the foods and beverages we consume are digested into glucose and enter the bloodstream, the pancreas releases insulin, which helps our cells use glucose for energy.

Insulin is also released in response to non-carbohydrate foods: protein and fat. Insulin is not the only hormone that helps regulate appetite and weight. High insulin levels are representative of an overall positive energy balance (eating too much).

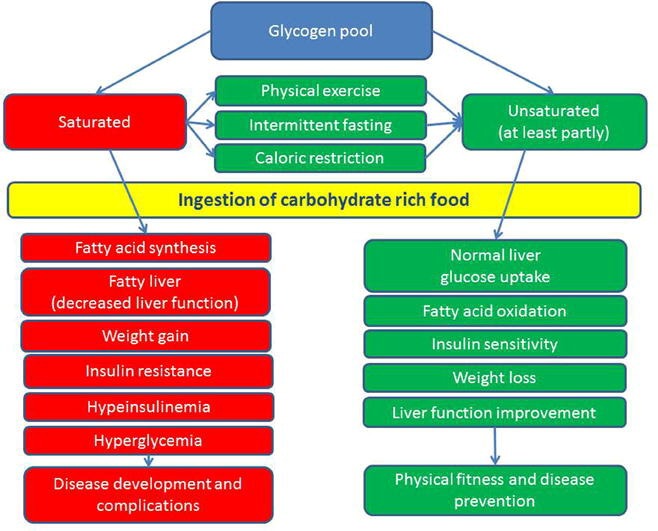

If excess glucose isn’t used, it's converted into glycogen and stored in the liver, muscle, and brain cells.

As these glycogen stores fill up, excess glucose gets stored in adipose (fat) cells. Carbohydrates and fats eaten together can accelerate fat storage as well, as the body preferentially uses the carbohydrates for quick energy and stores the fat. Sorry, donut fans.

To recap:

<ul role="list"><li>Your body’s first source of energy comes from any readily available glucose in your blood.</li><li>A secondary source of energy comes from the glycogen stored in your liver and muscles; you can burn through these stores through prolonged physical activity, caloric restriction, or intermittent fasting<sup>2</sup>.</li><li>As your glycogen stores deplete (as well as in some other circumstances), you tap into your stored body fat as an alternative energy source.</li></ul>

Our bodies use up glycogen stores to fuel physical and mental activities fairly easily, but as you may have experienced, it’s a lot harder to burn fat. Part of this difficulty is due to the fact that even a small rise in insulin from your baseline shuts down fat-burning processes. This is a simplification of an extremely complicated process:

Additional factors, such as the amount of glucose and how fast it enters the bloodstream, affect the speed and quantity of insulin released. More insulin released leads to the conversion of higher quantities of glucose to glycogen and fat.

A slow release of insulin in response to stable glucose levels means that you can replenish your glycogen stores with some or minimal conversion to fat.

A faster release of insulin means your body doesn’t have enough time to use glycogen, and most or all of the excess glucose gets stored as fat. The latter phenomenon typically results from high glucose spikes.

{{mid-cta}}

How Glucose Spikes Impact Insulin and Weight

A glucose “spike” is a rapid rise in glucose. It’s followed by a spike in insulin, which can cause your system to convert glucose rapidly to glycogen and fat. The rapid elimination of blood glucose can cause a state of mild hypoglycemia (lower than normal blood sugar).

As a result, you may feel hungry even if you ate recently. You may consume more food as your body attempts to restore your blood glucose to a normal range, and this can lead to a second glucose spike if you’re not careful about what, how much, and how quickly you eat. It’s ever-so-easy to snack on high-glycemic foods like soda and chips, which elevate your insulin level (again) and suppress fat burning.

The cycle of consuming more energy than your body uses—particularly from highly processed foods with a lot of added sugar—causes weight gain and an accumulation of excess fat.

When you gain fat mass, your body becomes less able to process high glucose spikes via a process called insulin resistance: when cells in your muscles, liver, and fat aren’t able to absorb glucose easily from your blood. As a result, your pancreas makes more insulin to help glucose enter your cells. As long as your pancreas can make enough insulin to compensate for your weakened insulin response, your glucose can stay in a healthy range.

Your body fights high glucose levels by increasing the amount of insulin produced—and this doesn’t do you any favors when trying to lose weight. When insulin remains high, your body misses the cue to burn through your glycogen and fat stores. This makes weight loss extremely challenging.

Conversely, a dip in insulin signals the body to burn glycogen or fat stores for energy.

When you keep blood sugar levels more stable by eating a healthy-for-you diet (we all respond to foods differently) and increasing physical activity, you reduce insulin resistance and can jumpstart weight loss.

Does Insulin Resistance Cause Excess Weight?

Generally, rates of excess weight and insulin resistance rise together, but which causes which remains controversial <sup>1,2,3,5-7, and many others</sup>.

Belly fat, or visceral fat, where your waist measurement exceeds 40 inches for men and 35 inches for women, is linked to insulin resistance. Scientists who studied 22 healthy women with a mean BMI of 27 found a strong relationship between abdominal fat and whole-body insulin sensitivity<sup>4</sup>. The association between belly fat and insulin sensitivity was much stronger than fat stored in other areas of the body.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of more than 60 studies helped investigate the link between insulin, chronic inflammation, and higher body mass index (BMI). Crucially, for weight loss, they found that in studies where participants decreased fasting insulin in the first part of the study, there was a significant subsequent decrease in BMI<sup>8</sup> in the second part of the study.

This meta-analysis lends credence to the idea that hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance is a potent driver of obesity and type 2 diabetes. It helps explain how a significant percentage of people with diabetes maintain a normal weight, but also that there are many who are obese and don’t have diabetes.

To sum, this is why insulin resistance can sabotage your weight loss efforts:

- When your body stops regulating glucose properly, you can develop insulin resistance. This means your cells stop responding to insulin effectively and are unable to use the glucose floating in your blood.

- Insulin resistance causes more glucose to circulate in the blood, resulting in chronically high blood sugar.

- High glucose in the blood signals the pancreas to release even more insulin.

For you, it means that the diet and activity changes involved in reducing insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia can be effective in lowering weight, too.

References

- https://aspenjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/

- https://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/45/5/633.short

- https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem

- https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI77812

- https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S280146

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/

- Item 1

- Item 2

- item 3