You may have heard of empty calories if you are trying to eat a healthy diet, but this term needs to be clarified for many to have a full understanding of the term. A food empty of calories sounds like it could be a helpful addition to your diet or considered a ‘free food’ when deciding what to include in your meal.

In reality, the term ‘empty calories’ describes foods with little or no nutritional value. Empty-calorie foods are usually higher in calories from added sugar, fat, or alcohol and have minimal amounts of protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) uses discretionary calories instead of empty calories.1 The DGA recognizes that added sugars and solid fats help with food preservation, texture, baking, cooking, and improving the taste of some less flavorful nutritious foods.

Discretionary calories are a more accurate term for explaining that a smaller portion of your daily intake ideally comes from foods low in nutrients. Each person can enjoy their ‘empty’ or ‘discretionary’ calories in a way that seems best for their lifestyle.

{{mid-cta}}

Macronutrients

No food or beverage is truly empty or without calories. Calories come from the macronutrients in food and drinks. Macronutrients means ‘big nutrients’ such as protein, carbohydrates, and fats that make up food and give the total calories when added together. Alcohol is not a macro but does provide a significant number of calories.1

- Protein and carbohydrates provide four calories per gram

- Fat provides nine calories per gram

- Alcohol provides seven calories per gram

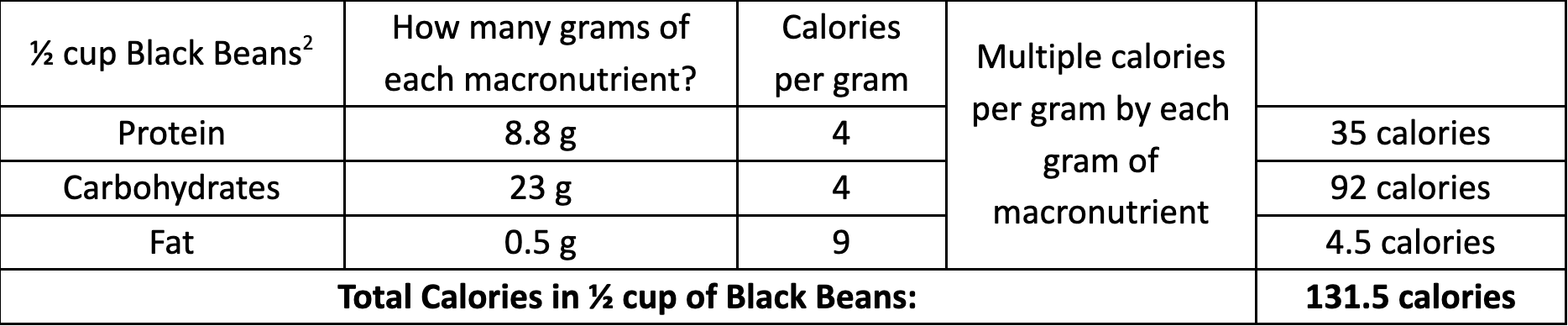

Let’s look at a food example. The nutrition label for a ½ cup of black beans states that this portion contains 131 calories.2 Here is how that number is calculated from the macronutrients present in black beans. Remember that rounding occurs in food labeling to ease reading the nutrition label.

Micronutrients

Micronutrients are also accounted for in foods. Micronutrients mean ‘small nutrients’ compared to the weight of the food, and macronutrients make up a larger portion of the weight. Micronutrients include vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients. For example, a ½ cup of black beans provides 32% of daily folate and 10% of daily iron needs.2

Calorie Density

The ratio of carbohydrates, protein, fat, and alcohol in food or beverages determines its calorie density. High-calorie density foods pack many calories in a small space (i.e., peanut butter or avocado oil). On the other hand, low-calorie density foods have relatively fewer calories in a larger amount of food (i.e., spinach leaves or celery).

Nutrient Density

While macronutrients affect calorie density, nutrient density is influenced by the ratio of micronutrients to calories in a food or beverage. Nutrient-dense foods contain a good amount of protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. These foods include fruit, vegetables, nuts, whole grains, beans, dairy or dairy alternatives, and protein (lean meat, poultry, fish, and eggs).1

Black beans are nutrient-dense due to their high protein, fiber, vitamin, and mineral intake. Nutrient-dense foods are more filling, partly from protein and fiber, providing a vitamin and mineral boost. Additionally, the nutrients found in these foods help prevent chronic disease.1

These food descriptions help to explain how foods are categorized as ‘empty’ or ‘discretionary’ calories and how to guide your food choices.

Are Empty Calories Better Than No Calories?

In terms of survival, any calorie source would be better than no calories. If allowed to choose the type of calorie source, empty calories or foods lacking protein, fiber, vitamins, and minerals should be limited for optimal health and chronic disease prevention.

The DGA recommends that most of the calories (85%) needed for optimal health should come from nutrient-rich foods to meet protein, fiber, vitamins, and mineral needs. The other 15% of the calories can be reserved for discretionary or empty calories like added sugars or fats.1

- Empty Calories Lack Micronutrients

It is challenging to meet nutrient needs and maintain a healthy weight if empty calories regularly comprise more than 15% of total intake. Empty calories tend to have fewer micronutrients, which, when eaten in excess, can lead to vitamin and mineral deficiencies over time while gaining weight. There is insufficient margin to meet nutrient needs and eat excess empty calories.

Similar to filling your 24 hours each day with activities, you have limited time available after sleeping and working. A day must be planned to make progress, or it could quickly be filled with lower priority or non-essential tasks that take up all your ‘discretionary’ time. Some days like this are helpful or restorative, but an excess of these days can lack purpose.

- Empty Calories Provide Less Fiber and Protein

Inadequate fiber and protein foods are often low in essential nutrients and high in caloric density. Fiber and protein help to help you feel full at meals or snacks and in between. When you don’t feel full, you tend to eat more.

A small study compared a diet full of empty calories to a nutrient-dense diet and how that affected healthy, weight-stable adults. The participants were allowed to eat as much or as little of the food. Individuals eating the empty-calorie diet averaged 508 more calories daily and gained two pounds after two weeks. While those consuming the nutrient-dense diet lost two pounds in the same time frame.3

- Empty Calories Lead to Health Problems

A higher rate of chronic disease is seen among individuals consuming excess empty calories. The lack of nutrients and excess fat and sugar can lead to weight gain, hinder weight loss efforts, and the development of heart disease, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, stroke, and depression. Over 50% of the calories from a usual American diet come from empty calories (or ultra-processed foods).4

Cross-sectional studies help determine disease prevalence at a specific time point among individuals. A large systematic review cross-sectional study including 113,753 participants found an association between those consuming the highest amount of empty calories or ultra-processed foods with a significant increase for overweight/obesity (+39%), high waist circumference (+39%), low HDL-cholesterol levels (+102%) and metabolic syndrome (+79%).4

This systematic review included prospective cohort studies evaluating 183,491 people for 3.5 to 19 years. They found that the highest empty calorie consumption was associated with an increased risk for death and increased incidence of heart disease, stroke, and depression.4

Food and Drinks That Contain Empty Calories

Balancing your nutrient-dense, whole foods with empty calories can allow you the flexibility to enjoy eating out at restaurants, socializing with friends and family, or baking sweet treats at home. Choosing nutrient-dense options for most of your intake will help you prevent disease, manage health conditions, and feel energized. Here are some sources of empty calories.

Heavy, Sugary, or Sweetened Foods

High sugar intake is associated with an increased rate of disease, including obesity, heart disease, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes.5 Sugar produces a strong glycemic response in the body and has been recently associated with the aggravation of inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, psoriasis, bowel disease, and chronic inflammation.5 Here are some foods typically high in added sugar from the DGA.1

- Soda or sugar-sweetened beverages like sweet tea, lemonades, coffee drinks, sports/energy drinks, or fruit drinks

- Cakes, cookies, donuts, and pastries

- Adding table sugar, honey, or syrup to foods

- Ice cream, desserts, and candy

- Breakfast cereals or cereal bars

Foods Loaded with Fats

Your body needs a certain amount and type of fat. Unsaturated fats in the form of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, along with omega-3 fatty acids, are recommended. Dietary fat in the form of saturated fat should be limited, and trans fat should be eliminated.6

Unhealthy trans fats and excessive saturated fats promote obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance, which can lead to the development of metabolic syndrome, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes.6 The DGA found that most Americans consume excess fat from the below sources:1

- Sandwiches (breakfast, breaded and fried chicken, lunch meat, burritos, tacos, burgers)

- Desserts and sweet snacks (baked goods or frozen desserts)

- Snack foods (crackers, chips)

- Casserole dishes

- High-fat dairy (cheese, whole milk, yogurt)

- Pizza

Other Foods with Empty Calories to Avoid

Keep an eye out for other foods that are considered empty calories.

- Processed meats like bacon, ham, hot dogs, and sausages

- Full fats like ice cream, butter, and whole milk

- Processed cheeses (American cheese or spray cheese)

- Fast food and pre-packaged condiments like barbeque sauce or ranch dressing

- Alcohol (beer, wine, and spirits)

How Many Empty Calories Can I Have a Day?

Now that you know what foods contain empty or discretionary calories, you may wonder how many to include in a balanced diet.

Remember, the DGA recommends 85% of calories to come from nutrient-dense sources and the other 15% from empty calories.1 Incorporating empty calories is important for baking, food texture, flavor, lifestyle flexibility, and the long-term sustainability of an eating plan. Lastly, empty calories are essential for enjoying some foods purely for their taste, like ice cream!

The average American adult has increased their empty calories (or as defined in the following study as ultra-processed foods) from 53.5% of their total intake in 2001-2002 to 57% of their total calories in 2017-2018.7 An extensive NHANES data evaluation of 40,937 American adults revealed over half of our calories are classified as empty calories.7

This study divided intake trends into four categories:

- Minimally processed (fresh, frozen, dry foods, grains, beans, and milk).

- Processed culinary ingredients like salt, sugar, and oils.

- Processed foods (canned fish or vegetables and cheeses).

- Ultra-processed foods (instant foods, ready-made sauces, dressing, French fries, chips, granola bars, soda, sugar-sweetened drinks, dairy and yogurt, cakes, cookies, sweet cereals, frozen foods, desserts, and more)

Americans are eating almost four times the number of empty calories than recommended for optimal health and to prevent the replacement of critical nutrient-dense foods.7 For adults trying to maintain a healthful diet, this equates to about 250 to 350 calories daily that can be allotted for empty calorie intake.1

Food with added sugar or excess fat will likely be an empty calorie. Look at the ‘Added Sugar’ on the food label and the percent daily value (DV) for added sugar. Try to keep the added sugar DV below 5%. This is considered low-added sugar.8

Reviewing the list of ultra-processed foods above and the lists provided in this article will help you to know what foods are considered empty calories. A good guideline is if the final food product looks similar to what the food looked like after it was grown or harvested, it is likely less processed with fewer empty calories and more nutrients.

Learn How to Make More Healthy Choices

Reducing empty calories to around 15% of your total daily calorie intake may seem daunting. Remember that this is a gradual process, and small steps in the right direction add up over time. You could reduce your empty calories from 50% of your total intake to 30% of your total intake. That is fantastic progress and will help prevent disease, maintain or achieve a healthier weight, and help you meet nutrient needs!

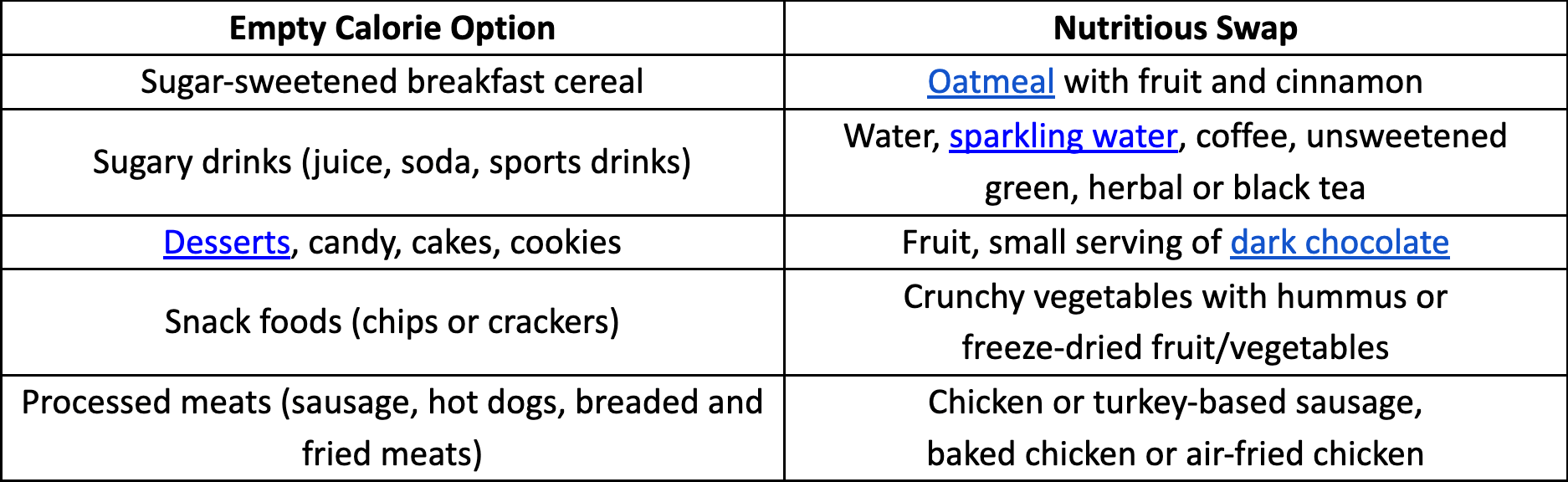

Simple swaps or substitutes can make a big impact and feel less overwhelming than an entire eating plan overhaul. Review your weekly intake of empty calories, and pick foods or drinks that could be an impactful swap. Sugary drinks are a great place to start.

Learn How to Choose Healthy Foods with Signos’ Expert Advice

Tools like a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) can help you keep track of your daily food intake and specific glucose response. Swapping empty calories for nutrient-dense options will reduce glucose levels and boost your nutrient intake. Knowing how your body responds to different foods helps your journey toward better health.

A Signos’ CGM can help you improve your health. Take a quick quiz to determine if Signos is a good fit for you. Learn more about nutrition and healthy habits on Signos’ blog.

- Item 1

- Item 2

- item 3

Topics discussed in this article:

References

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. Available at DietaryGuidelines.gov.

- USDA FoodData Central. (Oct 28, 2022). Food Details - Black beans, from dried, no added fat. Retrieved from https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/2342836/nutrients

- Hall, K. D., Ayuketah, A., Brychta, R., Cai, H., Cassimatis, T., Chen, K. Y., Chung, S. T., Costa, E., Courville, A., Darcey, V., Fletcher, L. A., Forde, C. G., Gharib, A. M., Guo, J., Howard, R., Joseph, P. V., McGehee, S., Ouwerkerk, R., Raisinger, K., Rozga, I., … Zhou, M. (2019). Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell metabolism, 30(1), 67–77.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008

- Pagliai, G., Dinu, M., Madarena, M. P., Bonaccio, M., Iacoviello, L., & Sofi, F. (2021). Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The British journal of nutrition, 125(3), 308–318. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520002688

- Ma, X., Nan, F., Liang, H., Shu, P., Fan, X., Song, X., Hou, Y., & Zhang, D. (2022). Excessive intake of sugar: An accomplice of inflammation. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 988481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.988481

- DiNicolantonio, J. J., & O'Keefe, J. H. (2017). Good Fats versus Bad Fats: A Comparison of Fatty Acids in the Promotion of Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, and Obesity. Missouri medicine, 114(4), 303–307.

- Juul, F., Parekh, N., Martinez-Steele, E., Monteiro, C. A., & Chang, V. W. (2022). Ultra-processed food consumption among US adults from 2001 to 2018. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 115(1), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqab305

- Added sugar. (2023, February 2). The Nutrition Source. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/carbohydrates/added-sugar-in-the-diet/

.jpg)